Published by Lookforzebras

- Misconception #1: It’s preventative medicine

- Misconception #2: It is not a “real” medical specialty

- Misconception #3: General preventive medicine is relatively new

- Misconception #4: It’s family medicine, internal medicine, or physiatry

- Misconception #5: It is just vaccines and screening tests

- Misconception #6: It is alternative, complementary, or integrative medicine

- Misconception #7: It’s not a clinical specialty

- Misconception #8: General preventive medicine is a fellowship

- Misconception #9: It’s only for doctors who have an MPH

- Misconception #10: It’s easy to get accepted

The specialty of general preventive medicine and public health is a great one. It comes with a broad array of career possibilities and work options that have major impacts on individuals and populations.

But it’s a field that suffers from misconceptions.

As a preventive medicine specialist myself, I spend quite a bit of time describing to people what it is that I do and what preventive medicine is. Here are ten common misconceptions that I’ve come across.

Misconception #1: It’s preventative medicine

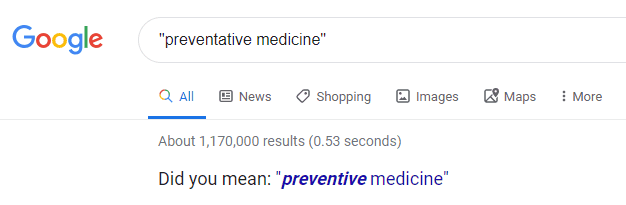

Many people say “preventative medicine” with a “ta” in the middle.

The truth: The specialty is general preventive medicine. Doctors in this field practice preventive medicine.

In almost all situations, the “ta” is unnecessary.

Even Google agrees:

The word preventative is sometimes used as a noun. For example:

It is a preventative, rather than a cure.

When describing this field of medicine or a type of intervention as an adjective, though, the term preventive medicine is preferred and more common.

Misconception #2: It is not a “real” medical specialty

The American Board of Preventive Medicine – who certifies physicians in general preventive medicine – is recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) as one of its 24 member boards.

This means that preventive medicine is just as much a medical specialty as internal medicine, neurology, dermatology, and other well-known specialties.

A doctor can do an ACGME-accredited residency in general preventive medicine, become ABMS-board certified in preventive medicine, and then say with confidence that they are a preventive medicine specialist.

Misconception #3: General preventive medicine is relatively new

There is a tendency for people to think that preventive medicine is a new specialty, simply because it’s not well-known and not talked about much.

In fact, the American Board of Preventive Medicine was first incorporated in 1948 and became a member board of the ABMS in 1949.

This means that it has been an ABMS-recognized specialty for longer than family medicine, allergy and immunology, nuclear medicine, thoracic surgery, emergency medicine, and medical genetics.

Misconception #4: It’s family medicine, internal medicine, or physiatry

When I tell people that my specialty is preventive medicine, responses such as these are common:

Oh, so you’re a family physician?

Or:

You’re trained in internal medicine, then?

While some preventive medicine specialists have completed a residency in both preventive medicine and family medicine or in both preventive medicine and internal medicine, this is not necessary. And, while family medicine and internal medicine training certainly includes some preventive medicine concepts, doing training in one is not the same as training in another.

Similarly, preventive medicine is frequently confused with physical medicine and rehabilitation. The reason for this is somewhat different than the confusion surrounding the connection with family medicine and internal medicine. A preventive medicine residency is often abbreviated “PMR,” and the specialty of physical medicine and rehabilitation is commonly known as “PM&R.” So the two get confused.

Misconception #5: It is just vaccines and screening tests

Preventive medicine is a lot more than common preventive health services like vaccines and cancer screening tests.

Clinical preventive healthcare strategies include:

Primary prevention – Methods targeting healthy, asymptomatic people to avoid the occurrence of disease (eg, a vaccine).

Secondary prevention – Methods to diagnose disease in early stages before it causes morbidity (eg, screening for high blood pressure).

Tertiary prevention – Methods to reduce the negative impact of disease by restoring function or minimizing disease-related complications (eg, a chronic disease management program).

Quaternary prevention – Methods to mitigate or avoid results of excessive or unnecessary interventions in the health system.

The specialty of preventive medicine includes much more than clinical preventive healthcare strategies, though. Its principal goal is to protect, promote, and maintain health and well-being and to prevent disease, disability, and premature death. To accomplish this, specialists must have knowledge and skills in overarching areas and concepts, such as:

- Epidemiological sciences and statistics

- Systems-based practice

- Healthcare management and administration

- Health policy, financing, and economics

- Population health

Misconception #6: It is alternative, complementary, or integrative medicine

Alternative medicine is any practice that is untested or not proven to be effective. Complementary medicine is non-mainstream medicine used together with conventional medicine. Alternative and complementary medicine is not formally taught in any ABMS-recognized specialties, though aspects come up from time to time in every medical field – including preventive medicine.

Integrative medicine is an approach to care that targets the whole person, including physical, emotional, lifestyle, biological, psychological, and spiritual aspects of well-being. A physician in any specialty can use this philosophy in their practice. While preventive healthcare and integrative medicine can often work symbiotically, they are not the same thing.

Neither alternative, complementary, nor integrative medicine is the focus of preventive medicine, and none of these is a significant part of preventive medicine training.

Misconception #7: It’s not a clinical specialty

Physicians are required to complete at least 10 months of direct patient care in both inpatient and outpatient settings prior to starting a preventive medicine residency. This is generally accomplished through a PGY-1 transitional year or a medical or surgical internship.

Then, as part of the preventive medicine residency program, residents continue to have clinical responsibilities.

The ACGME requires that preventive medicine residents have “educational experiences within a patient care environment that address direct clinical issues relevant to their area of concentration.” The requirements go on to say that each resident must have a “progressive responsibility for direct patient care.”

That said, the time spent in direct patient care during a preventive medicine residency is small in comparison to most other residencies. A preventive medicine residency alone won’t adequately prepare you for traditional primary care or hospitalist medicine.

The majority of doctors in the specialty of preventive medicine spend most or all of their time in non-clinical roles. They run health departments and work as medical directors outside of healthcare delivery settings, as a couple of examples.

Misconception #8: General preventive medicine is a fellowship

ACGME-accredited training programs in public health and general preventive medicine are residencies, not fellowships.

While you need to have at least completed a PGY-1 year before focusing on preventive medicine, there is no requirement that you complete an entire residency program prior to preventive medicine training or be board-eligible in another specialty.

Many physicians who pursue preventive medicine choose to do so after completing another residency. As such, it’s similar to doing a fellowship for them. But this is a choice rather than a requirement.

Misconception #9: It’s only for doctors who have an MPH

You do not need a Master of Public Health degree prior to acceptance into a preventive medicine residency program.

Most residencies include an MPH degree-granting program as part of the residency curriculum. This means you emerge from the residency as an “MD, MPH” or “DO, MPH.” But this is not a requirement.

Preventive medicine residency programs are required by ACGME to provide public health training, including epidemiology, biostatistics, health services administration, environmental health, and behavioral aspects of health. An MPH program is a good and efficient way to deliver this training. However, the completion of an equivalent degree is acceptable. As a few examples, this could be:

- MS in epidemiology

- MS in environmental science

- MS in occupational science

- Master of Health Administration (MHA)

- Master of Research (MRes)

Misconception #10: It’s easy to get accepted

Few doctors apply for preventive medicine residencies, mainly because they don’t realize it’s an option or because they have false beliefs about it. However, this doesn’t mean that it’s not competitive. There are several reasons that preventive medicine shouldn’t be considered an “easy” option:

Program size – Preventive medicine residency programs tend to be quite small. One reason for this is that their funding sources differ significantly from most other residencies, and available funds often limit the number of residents that a program can accommodate. A small change in the number of qualified applicants can have a big impact on whether you’re offered a spot.

Differences between training programs – Residency programs vary greatly in their foci and configuration. Some have far more options for public health courses and rotations than others. Those affiliated with top-rated schools of public health may offer more networking and research opportunities than others. Depending on your professional interests, getting into the program that will best prepare you for your career goals may not be a sure thing.

Application processes are becoming standardized – Few preventive medicine training programs go through the NRMP match program. This means that applicants need to apply separately to each program of interest. However, there is an effort taking place to standardize the acceptance process. I predict that the number of applicants will increase once this is accomplished and that each applicant will apply to more programs, on average.

Awareness of the field is increasing – The American Board of Preventive Medicine has recently become the certifying board for the new sub-specialties of addiction medicine and clinical informatics. With this comes a general awareness of preventive medicine and a greater interest in the field among students, residents, and practicing physicians.

Medical students and doctors are looking for alternatives – It’s increasingly common for medical trainees and doctors to consider unconventional career paths, including nonclinical jobs. Completing a preventive medicine residency opens up doors to many of the best nonclinical job opportunities. For this reason, I believe preventive medicine will become more competitive over time.

You now know more about the specialty of general preventive medicine than most people do – even many doctors. Do the field a favor by spreading the word!